Politics and Climate Change Conspire in South Africa’s Day Zero

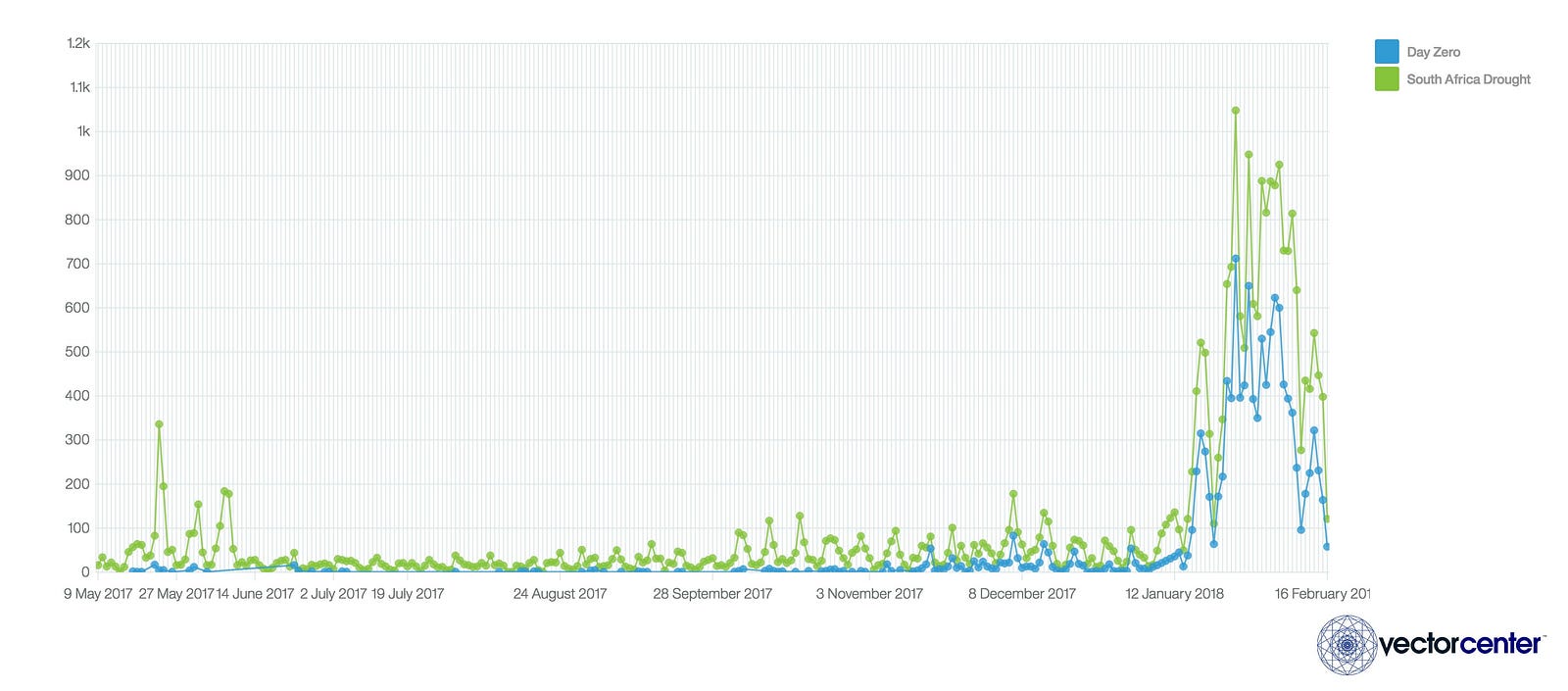

South Africa’s Western Cape and Cape Town are facing an unprecedented water shortage as the so-called Day Zero approaches.

The date, now pushed back to June 4, thanks to conservation efforts in the city, marks the day when the city effectively runs out of water, as reservoirs hit 13.5% or less of capacity.

When that happens, certain reservoirs, like the Theewaterskloof reservoir, will have to begin pumping water uphill, as they drain the depths of their supplies.

Cape Town relies nearly entirely on reservoirs for its water, with 99% of the city’s capacity coming from rainwater that fills the reserves. The city has no desalination plants and no groundwater pumping capacity, beyond a few privately held wells and boreholes.

Residents of Cape Town are now restricted to just 50 liters, or 13.2 gallons of water, per day for all personal needs, including bathing, drinking, cooking, showering, hand-washing, and toilets. The average American uses about 65.1 liters, or 17.2 gallons, per day just to shower.

Only a few years ago, Cape Town was lauded for its remarkable dam system and its efforts to fix leaky water infrastructure. But now, after a three year drought, once overflowing reservoirs sit empty.

Climate change likely played a role in the drought, though the direct links between the current drought and climate change haven’t been proven conclusively yet by scientists, due to the difficult nature of proving causal links to specific weather events.

Nonetheless, as late as 2014, historical records and trends suggested that a three-year drought in the Western Cape region had about a 0.1 percent chance. Despite the low risk, the drought came.

Water and Politics in South Africa

So, how did a city with the same population of Los Angeles get to this point? Politics and a reluctant population have both played a significant role.

The Western Cape province is the only province whose government is chiefly run by the main opposition party in the country: the Democratic Alliance (DA).

The majority party, the African National Congress, or ANC, controls all other provinces and the national government. Social-economic factors and history play a large role in this divide. The Western Cape region is an Afrikaans stronghold that has traditional voted against Nelson Mandela’s ANC.

This political divide, means that as the drought worsened, politics quickly took over, delaying response times and ultimately contributing to this current crisis.

Legally, the national government, not the local government, is responsible for providing water to every citizen in South Africa. Large scale changes to water infrastructure require the national government to act. Small scale projects, and rationing rules, are left to provincial and local governments.

Seeing a possible opening in the Western Cape, the ANC dragged its feet, and pointed fingers at the local DA government’s response to the drought throughout 2017, hoping to score an election win in 2019.

How these political games will play out at the polls, remains to be seen. What is clear however, is that the responses to the drought were slow, with little more than rationing being the only true governmental response.

In addition, the local population’s perception that water rationing wasn’t really necessary also contributed to the current situation.

As late as January 2018, long after the Day Zero concept had been announced to the public and rationing had begun, water consumption rates by residents remained high. With over 60% of residents exceeding the daily limit of then 87 liters, or 23 gallons, per day.

Rich South Africans too, with access rain catchment systems, have been able to skirt the restrictions, while poorer South Africans have suffered the most from the rationing.

Now it seems, the residents have finally taken the threat of Day Zero seriously, as their combined efforts have helped push back the date several times over the last two months. The end of the growing season has also helped the conservation efforts, with agriculture accounting for nearly 33% of the water consumption in the Western Cape.

June is fast approaching, and with it comes the rainy season, but for Cape Town, more than just rain is needed to mitigate this looming disaster.